| Home | Moli | Pelin | Lyna | Synopsis | Author |

|

MoLi - The first protagonist Mo Li is the daughter of an Imperial courtier. Her adventure begins even before birth when her mother is forced to flee Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion. Having survived the hazardous journey she finally arrives at Peony Land, the family estate in XiAn, where MoLi is born. Eight months old MoLi still awaits the arrival of her father from Beijing, but tied up with duties from the Imperial Court, he is unable to make his way to his family. When at last he succeeds in reaching Peony Land, he finds that his only child MoLi has been kidnapped by bandits. The distraught family use every means possible to find her and beg the Imperial Court to use official force. They contact Triade, investigate the child markets and the red light districts, all to no avail. Ten years later they by chance come to hear of a Chinese girl living with a British family and their desperate search finally comes to and end. They learn that the seven year old MoLi successfully managed to escape from her kidnappers and was found and adopted by a British family. MoLi feels caught between two lives and the people she loves. She struggles to reach a decision but ultimately her Chinese soul helps her to choose her original family. Years later she marries a military officer and moves to Shanghai with him. Shanghai is the start of a lonely life for MoLi as her husband is away a lot. During this time she bares three children, a boy and two girls, in the same hospital where she meets the British doctor Louis Smith-Sutton. Together they embark on an passionate love affair. Tragedy strikes MoLi once again with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War which robs her of her son who is shot during a demonstration. Her husband is absent and so she turns to Louis Smith-Sutton to help her overcome the grief. Ultimately the war forces MoLi to flee Shanghai and she once again finds herself facing great danger. She returns to Peony Land with her family, only to find that Japanese troops were there before them. They are greeted by an image of desolation and find that the estate has fallen victim to pillage, arson, rape and murder. Destroyed by grief, MoLi’s father passes away and her mother follows him only a short time after. MoLi feels like her family is falling apart. All the while her husband has been away fighting for the Chiang Kai-shek Army. The Communists are coming and he urges his family to leave China and make their way to Taiwan. MoLi however, adamantly refuses to part with her land and the family is thus labelled reactionary and persecuted accordingly...(read more)

China (Boxer Rebellion), 1900–01 - from Australian War Memorial During the nineteenth century the major European powers compelled the reluctant Chinese Empire to start trading with them. There was little the Chinese government wanted from the West at the time but there was a strong demand for opium among the population. In the Opium Wars of 1839-1842 and 1856-1860, the British forced the Chinese to accept the import of opium in return for Chinese goods, and trading centres were established at major ports. The largest of these was Shanghai, where French, German, British, and American merchants demanded large tracts of land in which they asserted "extra-territorial" rights, meaning they were subject to the laws of their own country not China. In Shanghai a legendary sign in a park near one of the European compounds read: "No dogs or Chinamen.". The Chinese government's failure to resist inroads on its sovereignty and withstand further demands from the Europeans, such as the right to build railways and other concessions, caused much resentment among large sections of the population. This eventually led to the Chinese revolution of 1911 which toppled the imperial dynasty. By the end of the nineteenth century the balance of the lucrative trade between China and merchants from America and Europe, particularly Britain, lay almost entirely in the West's favour. As Western influence increased anti-European secret societies began to form. Among the most violent and popular was the I-ho-ch'uan (the Righteous and Harmonious Fists). Dubbed the "Boxers" by western correspondents, the society gave the Boxer Rebellion its name. Throughout 1899 the I-ho-ch'uan and other militant societies combined in a campaign against westerners and westernised Chinese. Missionaries and other civilians were killed, women were raped, and European property was destroyed. By March 1900 the uprising spread beyond the secret societies and western powers decided to intervene, partly to protect their nationals but mainly to counter the threat to their territorial and trade ambitions. A04490A Boxer gun structure on the wall of the Imperial City. By the end of May 1900 Britain, Italy, and the United States had warships anchored off the Chinese coast at Taku, the nearest port to Peking. Armed contingents from France, Germany, Austria, Russia, and Japan were on their way. In June, as a western force marched on Peking, the Dowager Empress T'zu-hsi sent imperial troops to support the Boxers. Further western reinforcements were dispatched to China as the conflict widened. Australian colonies were keen to offer material support to Britain. With the bulk of forces engaged in South Africa, they looked to their naval contingents to provide a pool of professional, full-time crews, as well as reservist-volunteers, including many ex-naval men. The reservists were mustered into naval brigades, in which the training was geared towards coastal defence by sailors capable of ship handling and fighting as soldiers. 1 When the first Australian contingents, mostly from New South Wales and Victoria, sailed on 8 August 1900, troops from eight other nations were already engaged in China. On arrival they were quartered in Tientsin and immediately ordered to provide 300 men to help capture the Chinese forts at Pei Tang overlooking the inland rail route. They became part of a force made up of 8,000 troops from Russia, Germany, Austria, British India, and China serving under British officers. The Australians travelled apart from the main body of troops and by the time they arrived at Pei Tang the battle was already over.

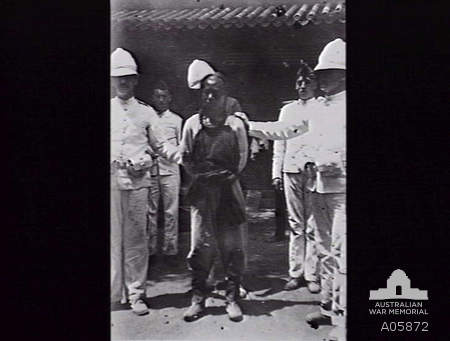

AWM A05872British servicemen hold their first Boxer prisoner. The next action in which the Australians (Victorians troops this time) were involved was against the Boxer fortress at Pao-ting Fu, where the Chinese government was believed to have sought refuge when Peking was taken by western forces. The Victorians joined a force of 7,500 on the ten-day march to the fort, only to find the town had already surrendered; the closest enemy contact was guarding prisoners. The international column then marched back to Tientsin, leaving a trail of looted villages behind them. While the Victorians marched to Pao-ting Fu and back, the NSW contingent was undertaking garrison duties in Peking. They arrived on 22 October, after a 12-day march. They remained in Tientsin and Peking over winter, performing police and guard duties and sometimes working as railwaymen and firefighters. Although they saw little combat, the Australian forces helped to restore civil order, which involved shooting (by firing squad) Chinese caught setting fire to buildings or committing other offences against European property or persons. The officers and men of the Australian contingents were dissatisfied with the nature of the duties they were asked to undertake. They had expected martial adventure and the opportunity to distinguish themselves in battle but had arrived too late to take part in significant combat.

The entire naval brigade left China in March 1901. Six Australians died of sickness and injury, and none were killed as a result of enemy action. While they had been away the colonies from which they sailed only nine months before had become a federal commonwealth and Queen Victoria died in England.

|

|

||

|